The oldest known translation of the Hebrew Old Testament is in Greek. In the centuries leading up to the coming of Christ, the Son of God, translation work had commenced on the Old Testament into Greek. The history of the early years and state of these works is hazy, with little remaining of its manuscripts to examine firsthand. As Timothy McLay put it, the evidence for the text of the Septuagint “that we actually possess” is “both fragmentary and corrupted.” Then he concluded:

“Occasionally, we might be able to justify an educated guess or conjectural emendation of what the text originally read, but the truth is that we do not know nearly as much as we might like; and in many cases we are reconstructing a majority text that may bear little resemblance to the original text.”[1]

Those words cannot be read without changing the opinions of countless people who have heard the word “Septuagint” and thought of a single entity, a book that can be picked up, handled, read, analyzed, and passed on. No such book exists now. The book on my bookshelf labeled “Septuagint” and the one under the same name available on Amazon is not, in fact, the Septuagint. It is a compilation, involving guesswork, of numerous late Greek translations and recensions. The factual evidence for this is documented below.

In attempting to recreate the so-called “Septuagint,” scholars are faced with fragmentary, corrupted texts, forcing them to guess at what an earlier version of the Septuagint contained. In the end, scholars realize that their monumental efforts to recreate a Septuagint text “may bear little resemblance to the original text.”

How can a person who comes to know these things not be astonished at all the claims? “Jesus quoted from the Septuagint” and “Paul quoted from the Septuagint” and “The New Testament quoted from the Septuagint” are statements that are so commonly repeated that they are not assumed without evaluation, but if the editions of the Septuagint available “may bear little resemblance to the original text,” on what basis can a person claim that Jesus quoted from the Septuagint? Our “Septuagint” confessedly rests on guesswork. The fact that some of His words align with the Septuagint becomes meaningless, for the Septuagint in hand today is formed from fragmentary, variable texts, mostly from material produced after Jesus Christ walked this earth as a human. Then the question becomes “who is quoting whom?” For, as we shall see below, what is called “the Septuagint” today is derived mainly from Greek recensions made after the first century, especially from the Old Testament portion of Codex Vaticanus. To say that Jesus quoted from the Septuagint based on His words aligning with words aligning with the words in the Septuagint on our bookshelf or computer program, without further qualification, is almost akin to saying that Jesus quoted from Codex Vaticanus, a manuscript commonly dated 300 years after Christ, for Codex Vaticanus is the main source and base text of Rahlf’s Septuagint, the most commonly used and cited version of the Septuagint.

To succinctly summarize the matter, all the manuscripts of the various Septuagint texts which predate the writing of the New Testament can all be held by a person’s right hand, with room left over to hold a pencil as well. If somehow these fragments were gathered out of their storage places from the museums and holders around the world and a person was given this privilege of holding these manuscripts in his right hand, he could look down at what he had, and he would see a handful of scraps. This is what scholars mean by “fragmentary.” They are faced with reconstructing a text that mostly does not exist (“fragmentary”). To bring this into our modern context, reconstructing the pre-New Testament “Septuagint” would be similar to reconstructing the entire 1,000 pages of the Old Testament portion of the King James Version from scraps of perhaps a few dozen fragmentary pages. Certainly, citations, references, and mentions exist of the early “Septuagint” versions (notice the plural), yet these are incomplete and always tenuous, as they are not the item itself, and often confusion ensues as to whether the early quotation is from the pre-New Testament Septuagint texts or from one of the later editions created after the New Testament was fully written, for, indeed, after the first century, numerous Greek recensions were created (see below). It is largely from these later ones that scholars attempt to reconstruct the earlier, pre-New Testament Septuagint texts, guessing backward as to the original. This would be akin to using the NIV, ESV, the New World Translation and perhaps an anonymous translation to reconstruct the Old Testament of the King James Version after all the copies of the King James Version had disappeared from earth except for fragments, an impossible task that once finished scholars understandably would confess “may bear little resemblance to the original [King James] text.”

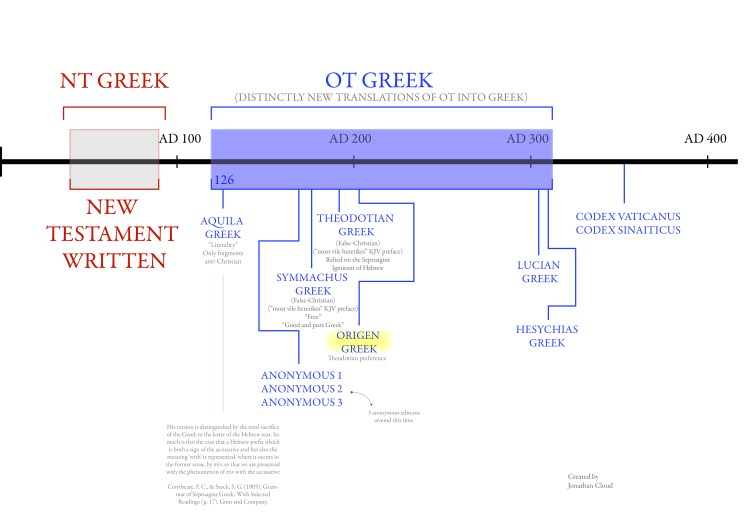

After the New Testament was written, at minimum 9 new “Septuagint” versions were created by the mid 4th century. The following chart documents these editions.

Thus, between the year AD 120 and the year AD 320, 9 new documented recensions or renderings were produced which differed from the original Septuagint texts.

- Aquila – AD 126

- Anonymous – 2nd century

- Anonymous – 2nd century

- Anonymous – 2nd century

- Symmachus – After Aquila in 2nd century

- Theodotian – 2nd century

- Origen – Early 3rd century

- Lucian – Early 4th century

- Hesychias – Early 4th century

The creation of these nine editions,[2] combined with the fact that these editions did not stay straight in their own lanes (being altered and even blended together in various ways over time),[3] form a barrier between modern scholarship and the pre-New Testament Septuagint. Of the Septuagint texts, Gleason Archer noted, “Yet it must be remembered that the LXX text has come down to us in various and divergent forms (such as to give rise to suspicions of a quite heterogeneous origin), and betrays a rather low standard of scribal fidelity in its own transmission. Greek scribes did not bind themselves to the same stringent rules of literal and meticulous accuracy as were embraced by the Jewish scribes of the period of the Sopherim….”[4] Then, Bednar wrote of the later manuscripts, “Errors in all extant LXX texts are many.”[5] Concerning Origen’s Hexapler text, the introduction to Zondervan’s Septuagint is noteworthy: “The Hexaplar text of the Septuagint was copied about half a century after Origen’s death by Pamphilus and Eusebius [c. AD 350]; it thus obtained a circulation; but the errors of the copyists soon confounded the marks of addition and omission which Origen placed, and hence the text of the Septuagint became almost hopelessly mixed up with that of other versions.”

Jerome, around AD 402, also recorded another scholar who had contributed to the confusion of the Septuagint. Jerome[6] wrote in his second Apology Against Rufinus, “I do not mention Apollinarius, who, with a laudable zeal though not according to knowledge, attempted to patch up into one garment the rags of all the translations, and to weave a consistent text of Scripture at his own discretion, not according to any sound rule of criticism.” [7]

Though traces of the shadowy figure of the pre-New Testament Septuagint exist, the last 1500 years are filled with complaints about its corruption. Consider the following sampling:

AD 400 ~ Jerome

Of Jerome’s witness in AD 400, John Owen wrote, “He that shall read and consider what Jerome hath written of this translation, even then when he was excusing himself, and condescending to the utmost to waive the envy that was coming on him upon his new translation, in the second book of his Apology against Rufinus, cap. viii. ix., repeating and mollifying what he had spoken of it in another place, will be enabled in some measure to guess of what account it ought to be with us. In brief, he tells us it is corrupted, interpolated, mingled by Origen with that of Theodotion, marked with asterisks and obelisks; that there were so many copies of it, and they so varying, that no man knew what to follow (he tells us of a learned man who on that account interpreted all the errors he could light on for Scripture); that in the book of Job, take away what was added to it by Origen, or is marked by him, and little will be left. His discourse is too long to transcribe.[8]

AD 1500-1700 Reformers

The Protestants of the Reformation viewed the Septuagint as corrupted, but not only the Reformers but their Catholic antagonists have been documented stating the same. (See the following entries)

AD 1500 Cardinal Xemenes

“If, moreover, the ability be granted [to the Septuagint translators], what security have we of their principlesand honesty? Cardinal Ximenes, in his preface to the edition of the Complutensian Bibles, tells us (that which is most true, if the translation we have be theirs) that on sundry accounts they took liberty in translating according to their own mind; and thence concludes, ‘Unde translatio Septuaginta duum, quandoque est superflua quandoque diminuta;’—’it is sometimes superfluous, sometimes wanting.’ But suppose all these uncertainties might be overlooked, yet the intolerable corruptions that (as is on all hands confessed) have crept into the translation make it altogether useless as to the end we are inquiring after.”[9]

AD 1600 Cardinal Ballermine

The Catholic Cardinal Bellarmine, council of Trent scholar (died 1621), said “that though he believes the translation of the LXX to be still extant, yet it is so corrupt and vitiated that it plainly appears to be another, lib. ii. De Verbo Dei, cap. vi.”[10]

As seen from this brief sampling, modern confusion concerning the “true reading” or “original reading” of the Septuagint is not new. The confusion went back to even the first century after the New Testament.

c. AD 150 Justin Martyr

The following account of Justin Martyr’s unique quotations from the Septuagint leans toward proving that the Septuagint was so confused in his day that he himself could not tell the real reading from the false or that the Septuagint is so confused in our day that we have no manuscript of it that has the original reading that Justin quoted.

“One of the most famous of these additions was inserted into the 96th Psalm. Justin Martyr, who was almost a contemporary of Aquila, quotes the tenth verse of that Psalm in a very remarkable form. In the Hebrew text it runs:

‘Say among the nations the Lord reigneth.’ Justin quotes the sentence in the form: ‘Say among the nations the Lord hath reigned from the Cross.’”

Another example is even more curious. Both Justin Martyr and Irenaeus quote, as coming from the Hebrew Scriptures, a sentence in Greek which may be translated as follows: ‘He came down to preach his salvation unto Israel, that he might save them’ – a verse obviously capable of a Christological interpretation. Both the Church Fathers named actually make such a use of it. Irenaeus quotes it from Isaiah, Justin from Jeremiah. Now, not only is there no such verse in the Hebrew Bible as known to us, but there is no such verse in any of the known copies of the Septuagint itself.”[11]

Examples of The Unreliability of What is Called the Septuagint

To give an example of the egregious errors in the Septuagint, as Harrison noted, “According to the chronology of the LXX, Methuselah survived the Flood by some 14 years, whereas the Masoretic text dated his demise in the year in which the Flood occurred (Gen. 7:23).”[12] This internal conflict of chronology, creating a 9th Flood survivor (over and above Noah and his sons and their wives), is an error that is not merely a different conclusion from the Masoretic Text, not only in conflict with all the testimony of Scripture concerning the Flood, but it is also a self-attested error, for the LXX also records that only 8 survived the Flood. Such a blunder in a matter that is obvious and objective should cause people to be wary of the LXX chronology in those areas where objective fact-checking may not be as readily available. The chronology of the LXX is objectively faulty, unlike that of the Masoretic text.

Yet, another question arises. According to the chronology of which “LXX” did Methuselah survive the Flood? Recalling the many versions that were produced before AD 320, which one or ones make such a blunder? The question itself highlights the fundamental point, that the LXX is not a single entity and to deal with it as such as no different than someone speaking of “the English Bible,” a quagmire of translations as divergent as The Message and the King James Version. Yet, as seen in Archer’s quote above, books, videos, and teachers commonly insinuate that the Septuagint is a single, homogeneous entity. Entire chronologies are being built upon today as if it was a single, unified entity like the Masoretic Text is.

AGE OF REHEBOAM ~ LXX agrees with, then contradicts the MT

Another example of the manifest errors of chronology in what is called the Septuagint is the age of Rehoboam.

1 Kings 14:21

– MT states Rehoboam was 41 when began to reign

– The LXX also states that he was 41 as well

1 Kings 12:24a

– The LXX states in its additional verses that Rehoboam was 16 years old when he began to reign

Reverse Quotations – Proof that the LXX quoted from the NT

John Owen long ago noted the tendency for the Septuagint to quote the New Testament: “Are foisted out of the Septuagint, as many places out of the New have been inserted into that copy of the Old.“[13]

One straightforward example of this is found in Psalm 14 (13 of the Septuagint). There, the common Septuagint text reconstructed by scholars places a lengthy section from Romans 3 into the Greek text of Psalm 14.

Here are Paul’s writings, with the Old Testament references to which he refers:

Romans 3:10 —- Psalm 14:3/Psalm 53:3

Romans 3:11 —- Ps. 14:2-4 (a summation of this) & Psalm 53:2-4

Romans 3:12 —- Psalm 14:3

Romans 3:13a/b —- Psalm 5:9/Psalm 140:3

Romans 3:14 —- Psalm 10:7

Romans 3:15-17 —- Isaiah 59:7-8 (Proverbs 1:16/Proverbs 6:18)

Romans 3:18 —- Psalm 36:1

Notice the numerous source passages for this section of Romans 3. Paul drew from at least 7 different places in the Old Testament in this compilation of instruction: Psalm 14, Psalm 53, Psalm 5, Psalm 140, Psalm 10, Isaiah 59, and Psalm 36. Yet, the “Septuagint” took his compilation and wedged all the verses into Psalm 14 (13).[14] So, if the translators of the Old Greek translations quoted Paul, why would it be surprising if they also quoted Jesus?

Other examples of this are found in various manuscripts and passages of the Old Greek translations. “For example, J. Ziegler notes that manuscript 764 has ἀνορθώσω instead of ἀναστήσω in Amos 9:11, which was obviously influenced by the presence of the quotations in Acts.”[15]

The Needed Proof

The many claims that “Jesus quoted from the Septuagint” or “Paul quoted from the Septuagint” would need the following proofs to validate them:

- A manuscript of the Septuagint that predates the New Testament

- This manuscript must contain a portion quoted by a New Testament passage

- The quotation would need to match

- And this quotation would need to differ from the Masoretic Hebrew text

Even if one such place was discovered, this would not prove the pattern. Proving a pattern takes a body of evidence.

In conclusion, showing that some of Jesus’ words align with these later Septuagint texts as found in a publishing house “Septuagint” is no evidence at all that He was quoting them.

[1] The Use of the Septuagint in New Testament Research p. 25 R. Timothy McLay, Eerdmans 2003

[2] The following description gives an idea of the differences between just three of these editions:

“These three interpreters took three different ways in the making of their versions. Aquila stuck closely and servilely to the letter, rendering word for word, as nearly as he could, whether the idioms and proprieties of the language he made his version into, or the true sense of the text, would bear it or no. Hence his version is said to have been rather a good dictionary to give the meaning of the Hebrew words, than a good interpretation to unfold unto us the sense of the text; and therefore Jerome commends him much in the former respect, and as often condemns him in the latter. Symmachus took a contrary course, and running into the other extreme, endeavoured only to express what he thought was the true sense of the text, without having much regard to the words; whereby he made his version rather a paraphrase than an exact translation. Theodotion went the middle way between both, without keeping himself too servilely to the words, or going too far from them; but endeavoured to express the sense of the text in such Greek words as would best answer the Hebrew, as far as the different idioms of the two languages would bear. And his taking this middle way between both these extremes is, I reckon, the chief reason why some have thought he lived after both the other two, because he corrected that in which the other two have erred. But this his method might happen to lead him to, without his having any such view in it. Theodotion’s version had the preference with all, except the Jews, who adhered to that of Aquila, as long as they used any Greek version at all.”

Prideaux, H. (1851). The Old and New Testament Connected in the History of the Jews (Vol. 2, pp. 56–57). Oxford University Press.

[3] For a brief example of this, consider this description by Prideaux: “And therefore when the ancient Christians found the Septuagint version of Daniel too faulty to be used in their churches, they took Theodotion’s version of that book into their Greek Bibles instead of it; and there it hath continued ever since. And for the same reason Origen in his Hexapla, where he supplies out of the Hebrew original what was defective in the Septuagint, doth it mostly according to the version of Theodotion.” Prideaux, H. (1851). The Old and New Testament Connected in the History of the Jews (Vol. 2, p. 57). Oxford University Press.

[4] Archer, Gleason. A Survey of Old Testament Introduction. Moody Publishers – A. Kindle Edition.

[5] Inerrancy Preserrved through Divine Providence, the Hebrew Masoretic Text by L. Bednar, D. Min. p. 76

[6] Of historical interest is the fact that Jerome, living in a day when the Septuagint was viewed as inspired, countered this with apostles and Christ, stating that the apostles and Christ did not follow the Septuagint, not even once, but always followed the Hebrew text. Here is a translation of his words: “The Hebrew Scriptures are used by apostolic men; they are used, as is evident, by the apostles and evangelists. Our Lord and Saviour himself whenever he refers to the Scriptures, takes his quotations from the Hebrew; as in the instance of the words ‘He that believeth on me, as the Scripture hath said, out of his belly shall flow rivers of living water,’ and in the words used on the cross itself, ‘Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani,’ which is by interpretation ‘My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?’ not, as it is given by the Septuagint, “My God, my God, look upon me, why hast thou forsaken me?” and many similar cases. I do not say this in order to aim a blow at the seventy translators; but I assert that the Apostles of Christ have an authority superior to theirs. Wherever the Seventy agree with the Hebrew, the apostles took their quotations from that translation; but, where they disagree, they set down in Greek what they had found in the Hebrew. And further, I give a challenge to my accuser. I have shown that many things are set down in the New Testament as coming from the older books, which are not to be found in the Septuagint; and I have pointed out that these exist in the Hebrew. Now let him show that there is anything in the New Testament which comes from the Septuagint but which is not found in the Hebrew, and our controversy is at an end.”

Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, eds. Theodoret, Jerome, Gennadius & Rufinus: Historical Writings. vol. III of A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series. Accordance electronic ed. (New York: Christian Literature Publishing, 1890), paragraph 20693.

[7] Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, eds. Theodoret, Jerome, Gennadius & Rufinus: Historical Writings. vol. III of A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series. Accordance electronic ed. (New York: Christian Literature Publishing, 1890), paragraph 20693.

[8] Owen, J. (n.d.). The works of John Owen (W. H. Goold, Ed.; Vol. 16, p. 418). T&T Clark.

[9] Owen, J. (n.d.). The works of John Owen (W. H. Goold, Ed.; Vol. 16, p. 417). T&T Clark.

[10] Owen, J. (n.d.). The works of John Owen (W. H. Goold, Ed.; Vol. 16, pp. 417–418). T&T Clark.

[11]https://dn790005.ca.archive.org/0/items/aquilasgreekvers00abrarich/aquilasgreekvers00abrarich.pdf, accessed 2025 07 21

[12] Harrison, R. K. (1969). Introduction to the Old Testament (p. 149). Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

[13] Owen, J. (n.d.). The works of John Owen (W. H. Goold, Ed.; Vol. 16, pp. 366–367). T&T Clark.

[14] Psalm 13:3 expansion in LXX:

τάφος ἀνεῳγμένος ὁ λάρυγξ αὐτῶν ταῖς γλώσσαις αὐτῶν ἐδολιοῦσαν ἰὸς ἀσπίδων ὑπὸ τὰ χείλη αὐτῶν ὧν τὸ στόμα ἀρᾶς καὶ πικρίαςγέμει ὀξεῖς οἱ πόδες αὐτῶν ἐκχέαι αἷμα σύντριμμα καὶ ταλαιπωρία ἐν ταῖς ὁδοῖς αὐτῶν καὶ ὁδὸν εἰρήνης οὐκ ἔγνωσαν οὐκ ἔστιν φόβοςθεοῦ ἀπέναντι τῶν ὀφθαλμῶν αὐτῶν

Romans 3:13-18 in the TR

13 τάφος ἀνεῳγμένος ὁ λάρυγξ αὐτῶν, ταῖς γλώσσαις αὐτῶν ἐδολιοῦσαν. ἰὸς ἀσπίδων ὑπὸ τὰ χείλη αὐτῶν. 14 ὧν τὸ στόμα ἀρᾶς καὶ πικρίας γέμει. 15 ὀξεῖς οἱ πόδες αὐτῶν ἐκχέαι αἷμα. 16 σύντριμμα καὶ ταλαιπωρία ἐν ταῖς ὁδοῖς αὐτῶν, 17 καὶ ὁδὸν εἰρήνης οὐκ ἔγνωσαν. 18 οὐκ ἔστι φόβος Θεοῦ ἀπέναντι τῶν ὀφθαλμῶν αὐτῶν.

[15] The Use of the Septuagint in New Testament Research p. 25 R. Timothy McLay, Eerdmans 2003